Definition

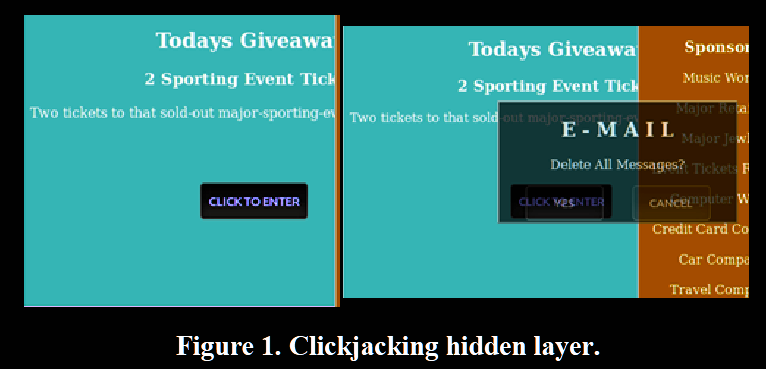

Clickjacking, previously known as UI Redress attack, is a term first introduced by Jeremiah Grossman and Robert Hansen in 2008 to describe a technique whereby cross-domain attacks are performed by ‘hijacking’ user-initiated mouse clicks to perform actions that the user did not intend (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

Clickjacking attacks merge malicious UI elements with non-malicious UI elements, or transparently trick the browser into sending input to a malicious server or function call, rather than an intended function call

- Often, iframes and CSS techniques are exploited to create the invisible layer

There are many methods of attacking an application using clickjacking, with JavaScript, HTML, and CSS.

- Clickjacking attack are considered a form of user-interface keylogger

When used against unsuspecting end users, clickjacking attacks can allow an attacker to steal valuable user input (sensitive data, financial transactions, etc…)

Requirements

- The user has to click to a malicious link which points to a legitimate-looking website (may be a copy of a real trusted website)

- The fake website contains invisible iframes and the actions of the user are captured by this invisible layer without him being aware of it

JavaScript may also be used to position the iframe under the mouse cursor, such that the user will click on the target no matter where they click on the malicious page. (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

The victim action on the transparent layer looks “safe” from the browser’s point of view, because the SOP (Same-Origin Policy) it is not technically violated (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

Contrarily to SQLIA (SQL injection attack), clickjacking does not depend on a bug in the application, such as an input validation failure, but it is just a misuse of HTML/CSS features to trick an user (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

Risks and consequences

Camera and microphone exploit in Adobe Flash, 2008 The user:

- was mislead to play a web game, by clicking on a malicious link

- every click within this game corresponded with a click on a Adobe Flash settings page, that was embedded in a iframe

- When interacting with the clickjacking web page, the end user was tricked into passing clicks through to the privileged Adobe Flash privacy settings

- The result was that the Adobe Flash browser plug-in would share both camera and microphone control with the hacker

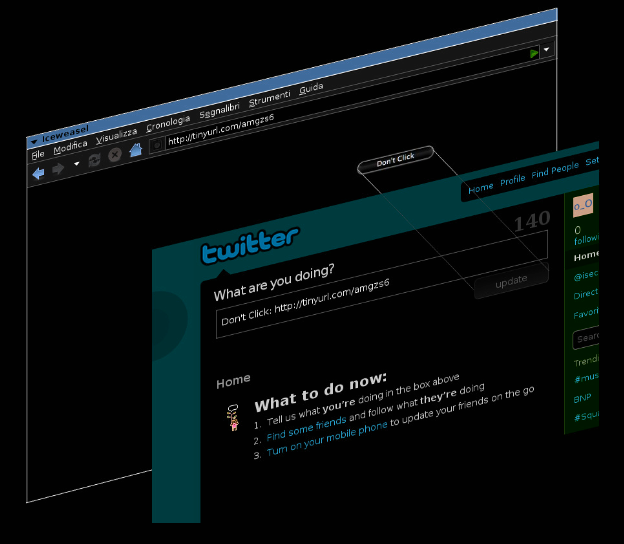

Attackers have used clickjacking attacks to trick users into liking a fan page on Facebook or re-tweeting a message on Twitter (Hazhirpasand, 2020)

Tweetbomb and likejacking (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015)(Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013)

- using clickjacking to trick an user to like a post on Facebook or share a post Tweeter, causing an increase of traffic to the attacker’s content

From (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010):

- initiate money transfers

- clicking on banner ads that are part of an advertising click fraud

- posting blog or forum messages

From (Onarlioglu, Buyukkayhan, et al., 2015): clickjacking attacks can be launched from malicious legacy browser’s extensions

From (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013): clickjacking attacks can lead a victim buying items on Amazon or performing undesired financial transactions

Prevalence

Only 930 pages out of 1.065.482 websites contained invisible iframe (0.16%) (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

Clickjacking classification

Compromising target display integrity (Hazhirpasand, 2020) (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

- a sensitive UI is hidden/made invisible and an attractive decoy is placed over or beneath it, nudging the user to interact with it

Compromising pointer integrity (Hazhirpasand, 2020) (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

- a fake cursor (pointer) is used instead of the real cursor

Compromising temporal integrity attack (Hazhirpasand, 2020) (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

- the sensitive element is not hidden, the users can potentially see it but are nonetheless tricked into making an unwanted click because they are engaged in a distracting activity. Humans need at least a few hundred milliseconds to react to a sudden visual change

- online games are a perfect example of this attack. Hackers can exploit this situation to get access to webcam, or to bypass security captcha embedded in an iframe

- an hidden iframe may be added in front of the mouse just before the user performs the click and removed just after (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

Advanced attacks

From (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013):

- Multiple iframes: will bypass the frame busting code technique

- Event handler overriding: a malicious popup could be displayed as the user tries to close or reload the page (

onBeforeUnloadevent is executed when a page is about to be unloaded) - No-content response (204): legacy browsers mishandled HTTP 204 responses in the context of iframes. In some cases, if a website responded with

X-Frame-Options: DENY, the iframe would be blocked from loading as expected. However, by sending repeated requests that were responded with HTTP 204, the browser could enter an inconsistent state and end up forcing the original URL to load in the iframe, temporarily ignoring security headers like X-Frame-Options. This security issue is now fixed - Reflective XSS (cross site scripting)

- DOM clobbering can be used to pollute global objects used in frame busting code (

top.locationcan be overwritten by an attacker) - Disabling JS in iframe using

sandbox: this is a double-edged sword because it can protect against malicious iframe code but, at the same time, legitimate frame busting code in the legitimate iframe will not be executed.

Mitigation techniques

- The HTTP Content-Security-Policy (CSP) frame-ancestors directive specifies valid parents that may embed a page using

<frame>, <iframe>, <object>, or <embed> - Setting this directive to ‘none’ is similar to X-Frame-Options: deny (which is also supported in older browsers).

Frame busting (Hazhirpasand, 2020) (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016) (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015) (Sood, Enbody, et al., 2011) (Sinha, Uppal, et al., 2014) (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013) Frame busting is a technique to prevent a given web page from being loaded in a sub-frame. Many JS snippet have been proposed to implement that solution

- given that is a client-side implementation, it can be modified by an attacker, so does not really protect against a well-crafted targeted attack

- using the

sandboxattribute would allow an attacker to bypass the framebusting1 - using nested iframes could break the logic, given that even if the second iframe is reloaded and takes the place of the first iframe, the legitimate content is still framed

- third-party embeddable widgets, such as Facebook like button are not inside an iframe and are therefore still exposed (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013):

// framebusting example

// window.self === self

// window.top is the topmost window on the iframe stack

if (window.top != window.self) {

// if your website is embedded in an <iframe> this will force the page to reload. The malicious website is replaced with the legitimate one

top.location.href = location.href;

}Rigid clickjacking prevention are challenging to implement by browser vendors, because it is not easy to distinguish between a legitimate and a malicious usage of iframe (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

X-Frame-Options on HTTP header

using X-Frame-Options header in HTTP will prohibits a website from being rendered in a iframe. (Aditya Sood, Richard Enbody, et al., 2011) ,(Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016), (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015) , (Sood, Enbody, et al., 2011) (Sinha, Uppal, et al., 2014), (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

- only 11.11% of Alexa’s top 1 million sites implement

X-Frame-Optionsheader - Header-based solutions are difficult to scale up for organizations hosting multiple websites referring each other (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015)

- By-passable with proxies (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013):

Confirmation dialog (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015) (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013) A confirmation dialog has been proposed to mitigate clickjacking attacks when there is a possible out-of-context click.

- the user experience is degraded and the user is involved in a security measure that should be his responsibility

GUI randomization (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015), (Sinha, Uppal, et al., 2014) (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013) Randomizing the layout of small part of the UI to prevent an attacker to correctly locate the position of the target element

- the user experience is degraded

- the performance of the page is degraded

Blocking of mouse click (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015) (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013) Blocking the mouse if browser detects that the clicked cross-origin frame is not fully visible

Browser plugins/extensions (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015), (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013)

- ClickIDS for Firefox: to detect overlapping clicks by comparing the mouse position to the position of clickable elements inside an iframe. The user is warned when an overlap is found (implemented by (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010))

- Noscript: disables all JavaScript elements. It can degrade the user experience or prevent the user to fully access all the functionalities of a web application

- WebOfTrust: passively prevents clickjacking attacks by discouraging users to visit malicious web pages that are potentially framing legitimate websites in iframes. The tool relies on user ratings of malicious websites.

Client-side proxy (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015)

- The approach intercepts requests and responses and uses a set of policies to examine for matching with known clickjacking attacks. The approach delays the generation of response pages due to rigorous checking of JavaScript code.

From (Sinha, Uppal, et al., 2014):

- ProClick: a client-side proxy that analyzes a web page for clickjacking symptoms before its rendering. It leverages on the HTTP communication to detect iframes (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013)

- ClearClick: a browser plugin that monitors the page behavior during click actions. If a user is about to click on a page that has been framed or on a plug-in object, ClearClick takes a screenshot of the iframed page with opacity as zero. This screenshot is compared to the parent page’s screenshot and if any difference is found in the two images the click action is prevented (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

Limits of existing studies

- Not all the possible ways to embed a cross-site application have been studied

- Most of the work focuses on the

<iframe>tag, but also<object>and<embed>can be used

References

- (Hoffman, 2024)

- Included in literature review, by (Onukrane, Skrodelis, et al., 2023)

- Granting web permissions, by (Hazhirpasand, 2020)

- (Selim, Tayeb, et al., 2016)

- Short literature review, by (Sinha, Uppal, et al., 2014)

Related to clickjacking in project SLR:

- (Lv, Shi, et al., 2023)

- (Gelernter, Grinstein, et al., 2015)

- (Shahriar, Haddad, et al., 2015)

- (Onarlioglu, Buyukkayhan, et al., 2015)

- (Shahriar, Devendran, et al., 2013)

- (Chandra, Kim, et al., 2011)

- (Sood, Enbody, et al., 2011)

- HTTP header example from (Aditya Sood, Richard Enbody, et al., 2011)

- (Balduzzi, Egele, et al., 2010)

- (Stamm, Sterne, et al., 2010)